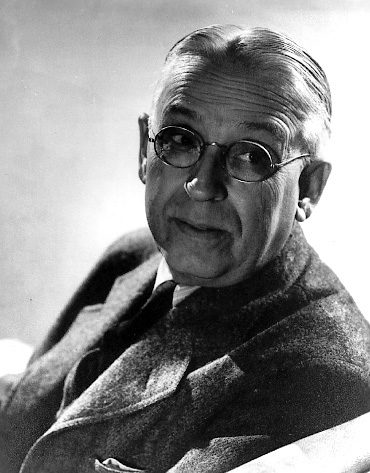

ARTHUR SHEPHERD, Composer, 1880–1958 1977 CLEVELAND ARTS PRIZE FOR MUSIC (POSTHUMOUS)

Despite his affection for indigenous themes, however, Shepherd never abandoned the classical European techniques he mastered at the New England Conservatory of Music in Boston, where he studied from age 12 to 17. “He was a traditional composer, out of step with the newest expressions of his time,” wrote musicologist Richard Loucks in his well-balanced biography, Arthur Shepherd: American Composer. “Shepherd adhered to the primacy of consonance and tonality—yet his methods of creating a ‘key’ and his uses of all the intervals are fresh and individual.” During his lifetime, Shepherd’s music was performed by leading orchestras, solo artists and chamber music ensembles. Although his meticulously crafted works are seldom programmed today, some of his music is preserved on excellent recordings, including CRI American Masters discs that were originally released on LPs by Western Reserve University, and a more recent collection on Tantara, a Utah-based label devoted to Mormon composers. Shepherd began his professional career in Salt Lake City. Having been a teenage prodigy, he taught music, wrote prize-winning compositions and conducted symphony and theater orchestras. In 1909, he joined the faculty of his alma mater in Boston. During World War I, he led a United States army band in France. After the war, he returned to Boston, where his marriage to Hattie Jennings of Salt Lake City ended in divorce. In 1920, he accepted an invitation from Cleveland Orchestra music director Nikolai Sokoloff to become the orchestra’s assistant conductor and program book editor. Several works of his were performed by the orchestra. Although Shepherd relinquished his conducting duties six years later to take a teaching post at Cleveland College of Western Reserve University, and later heading the university’s music department, he continued to write program notes for the orchestra, and he also served briefly as music critic of The Cleveland Press. In 1922, he married Grazella Puliver, a distinguished Cleveland educator and founder of Cleveland College, who shared his love of nature and his gift for cultural conversation. Living Room Learning was one of her initiatives. Shepherd taught at the university until 1950 when he retired to devote more time to composition. In his book, Reflections on Composing: Four American Composers, 1977 Cleveland Arts Prize winner Frederick Koch wrote of his mentor, “He might be described as a serious professorial type; but there was always a twinkle in his eye, for he had a keen sense of humor.” Shepherd revealed his lighter side in Domestic Symphony, a musical joke he composed for his longtime patrons, Dudley and Elizabeth Bingham Blossom. Following Shepherd’s death on January 12, 1958, Plain Dealer music critic and 1961 Cleveland Arts Prize winner Herbert Elwell eulogized his admired colleague as “a composer in the fine tradition of such Americans as MacDowell, Chadwick, Hadley, Converse and Arthur Farwell” and as an “inspirational teacher and an indefatigable organizer of many important musical enterprises.” Earlier, Cleveland Press critic and 1968 Cleveland Arts Prize Special Citation winner Arthur Loesser lauded Shepherd as “one of the most outstanding musicians ever to have graced Cleveland by living here.” High praise, indeed, from distinguished musical contemporaries. —Wilma Salisbury

|

Cleveland Arts Prize

P.O. Box 21126 • Cleveland, OH 44121 • 440-523-9889 • info@clevelandartsprize.org

Arthur Shepherd, like other esteemed composers of

his generation, sought to develop a distinctively American musical

language. Born in the Mormon village of Paris, Idaho, on February 19,

1880, he celebrated his pioneer heritage in works such as

Arthur Shepherd, like other esteemed composers of

his generation, sought to develop a distinctively American musical

language. Born in the Mormon village of Paris, Idaho, on February 19,

1880, he celebrated his pioneer heritage in works such as