Cleveland School of the Arts, Inspiring Example for Urban Education 1996 SPECIAL CITATION FOR DISTINGUISHED SERVICE TO THE ARTS

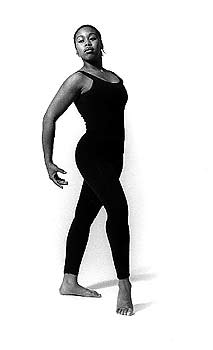

The school, then 15 years old, had already distinguished itself as a place where small miracles happened every day. Children who didn't succeed in conventional classrooms found a place to be themselves. At-risk children from some of Cleveland's meanest streets reinvented themselves as actors, painters, photographers, dancers, writers and musicians. In a safe and nurturing environment, they were free to explore their emotions, conquer their fear and dream of a better future. Among their teachers were distinguished professionals who imparted the values of hard work, creativity and sensitivity. Artists-in-residence filled in the blanks, giving the benefit of their own life experiences. Core curriculum teachers were equally creative, using visual, literary and performance art to enhance studies in math, social studies, science, and history. Their brick schoolhouse on University Circle was no Shangri-la, however. In fact, the building was nearly a century old and a shambles. The roof and windows were so dilapidated, it was not uncommon to feel wind, rain and snow in the classrooms. The fourth floor was unusable. Plaster fell from ceilings and moisture threatened the musical instruments. Barbara E. Walton, who arrived that year as assistant principal, recalled asking after her first building tour, “Who did you guys make mad downtown?” But the children threw on extra sweaters and saw a unique opportunity. That they had been selected from hundreds of candidates indicated a vote of confidence. That they had been invited to stay for six years, with the same teachers and peers, instilled a sense of comfort. That their teachers were prepared to mentor them right through the college application process suggested their dreams might just come true. Walton went on to become principal of the school, whose enrollment over the next seven years climbed to 702 students. During the first decade of her tenure, which ended in 2011, students performed for two U.S. presidents and traveled to Japan and Austria for concerts. They were the only high school group invited to the prestigious Innsbruck Festival in 1999. The children helped raise travel money by performing a benefit concert at Severance Hall, home of the Cleveland Orchestra. And the school's talented dance troupe, Y.A.R.D. (Youth at Risk Dancing), won praise from Time magazine.

The school also enjoys corporate partnerships with the Cleveland Plain Dealer, local universities and the many arts organizations in their culturally well-endowed neighborhood. Volunteers from the Plain Dealer have come into the building to help paint the school's interior; and the Cleveland Play House hosts a much-touted playwriting festival, conceived, designed and performed by the school's students. In gratitude for the opportunities, students excel. According to 2002 statistics, not only do they show up (95 percent attendance), they graduate (100 percent) and go on to higher education (94 percent to college; 6 percent to the armed forces). One young man who lived under a bridge when he was accepted to Cleveland School of the Arts is now a professional dancer. Another graduate landed a lead role in the touring company of The Lion King. Another, who founded a music production company, has invented a music system for churches that cannot afford a musical instrument. Another is designing cars at Ford Motor Company. Three graduates have chosen careers that provide the most eloquent testimonial to the schoolhouse of small miracles: They are now teachers at the Cleveland School of the Arts. —Faye Sholiton |

Cleveland Arts Prize

P.O. Box 21126 • Cleveland, OH 44121 • 440-523-9889 • info@clevelandartsprize.org

No prizes were awarded by the Cleveland Arts Prize

in 1996. Instead, the organization used the occasion of Cleveland's

Bicentennial to put the community on notice that its creative future

was being jeopardized by the cost-cutting elimination of programs that

exposed Cleveland school children to the arts and to the rewards of the

creative experience. The Arts Prize underscored its point by awarding a

Special Citation for Distinguished Service to the Arts to the Cleveland

School of the Arts, a magnet school within the Cleveland Municipal

School District.

No prizes were awarded by the Cleveland Arts Prize

in 1996. Instead, the organization used the occasion of Cleveland's

Bicentennial to put the community on notice that its creative future

was being jeopardized by the cost-cutting elimination of programs that

exposed Cleveland school children to the arts and to the rewards of the

creative experience. The Arts Prize underscored its point by awarding a

Special Citation for Distinguished Service to the Arts to the Cleveland

School of the Arts, a magnet school within the Cleveland Municipal

School District. None

of the school's achievements would be possible on the Cleveland public

school's meager budget. Since 1984, the school has been blessed with a

Friends group that has helped provide summer scholarships, internships,

private lessons, musical instruments, grant-writing expertise and

artists' residencies. Thanks in large part to the Friends' $1.3 million

donation, six classrooms have been restored on the fourth floor, and

all windows are now state-of-the-art.

None

of the school's achievements would be possible on the Cleveland public

school's meager budget. Since 1984, the school has been blessed with a

Friends group that has helped provide summer scholarships, internships,

private lessons, musical instruments, grant-writing expertise and

artists' residencies. Thanks in large part to the Friends' $1.3 million

donation, six classrooms have been restored on the fourth floor, and

all windows are now state-of-the-art.