David E. Davis, Sculptor, 1920–2002 1980 CLEVELAND ARTS PRIZE FOR VISUAL ARTS

The artist’s deep respect for orderly thought and critical analysis can be traced to his Rumanian childhood as the son of a noted Talmudic scholar. For Davis, discipline and a logical structure were always essential to his art. In 1934, with the shadow of Naziism spreading across Europe, his family relocated to Cleveland. There David won a full scholarship to the Cleveland School (now Cleveland Institute) of Art just as war was breaking out in Europe, only to have his studies interrupted by four years in the U.S. Armed Forces. After the war he attended the École des Beaux Arts in Paris and the Cleveland Institute and went on to earn a master of fine arts from Western Reserve University in Cleveland.

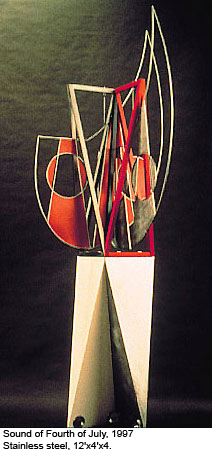

But it was not until 1967—after stints as vice president for Cleveland-based American Greetings Corporation’s Creative Department and vice president of Electro General Plastics—that Davis set up a metal-working studio in a former gasoline station so he could devote himself to sculpture full time. Over the next three decades, his work would be featured in more than 19 solo and numerous group exhibitions in venues ranging from the Cleveland Museum of Art and the Butler Institute of American Art to galleries and museums in Florida, New York, Chicago and Bucharest, Rumania. Davis executed a number of major public commissions in Ohio and Florida, and his work is represented in many museum collections including those of the Israel Museum in Jerusalem, the John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art, the Cleveland Museum of Art, as well as in significant private and corporate collections. He preferred to work in a series, defining a general theme around which visual ideas were explored. The aesthetic qualities of a work—form and color—along with the material itself (typically cast bronze or fabricated metal elements carefully welded, polished and painted) were more interesting to him than content. Most comfortable working in an abstract idiom, he sought to create timeless visual symbols from a specific vocabulary of forms ranging from geometric to organic, often combining the two. “My overall aim,” he said, “is one of harmony, peace and beauty.” During the 1970s, Davis pursued his Harmonic Grid Series and its almost limitless possibilities. After winning the Cleveland Arts Prize in 1980, he spent the next two decades exploring the tetrahedron, arch and spiral. As the geometric edge of his early work softened in the Arch Series, he shifted from constructed pieces to carved pieces, and from metals to wood and stone. Davis also had a deep commitment both to the advancement of his chosen art form and to the preservation of the region’s distinctive cultural heritage. In 1990 he and his wife, Bernice Saperstein Davis, co-founded the Sculpture Center, a resource and exhibition space, to nurture promising area sculptors, and, in 1997, the Artists Archives of the Western Reserve. Davis Davis died in November 2002. He was 82.

—Dennis Dooley For more about the artist, or to see other examples of his work, visit: The Sculpture Center Artist Archives of the Western Reserve |

Cleveland Arts Prize

P.O. Box 21126 • Cleveland, OH 44121 • 440-523-9889 • info@clevelandartsprize.org

Making more with less was the driving idea behind the work of David E. Davis. In the 1970s, using a deliberately

restricted visual vocabulary of triangles, circles and rectangles—which

he subdivided, combined and juxtaposed in a system he called the

Harmonic Grid—he created pieces that ranged from the monumental to the

dynamic. Indeed, the fluid rhythms achieved in many of his pieces

evoked comparisons with music.

Making more with less was the driving idea behind the work of David E. Davis. In the 1970s, using a deliberately

restricted visual vocabulary of triangles, circles and rectangles—which

he subdivided, combined and juxtaposed in a system he called the

Harmonic Grid—he created pieces that ranged from the monumental to the

dynamic. Indeed, the fluid rhythms achieved in many of his pieces

evoked comparisons with music.