Frederick A. Miller,

1968 CLEVELAND ARTS PRIZE FOR VISUAL ARTS

The fascination with mass-produced, identical products—from

automobiles to tableware—that swept America in the early years of the

20th century made millionaires of men like Henry Ford, who, if he did

not invent, at least perfected assembly line production. Frederick A.

Miller preferred to think of this fascination as a kind of national

“trance.” Fortunately for him, there were still individuals who

appreciated owning one-of-a-kind objects. And when that involved

silver, few artisans were his equal.

The fascination with mass-produced, identical products—from

automobiles to tableware—that swept America in the early years of the

20th century made millionaires of men like Henry Ford, who, if he did

not invent, at least perfected assembly line production. Frederick A.

Miller preferred to think of this fascination as a kind of national

“trance.” Fortunately for him, there were still individuals who

appreciated owning one-of-a-kind objects. And when that involved

silver, few artisans were his equal.

Born in Akron in 1913, he moved to Cleveland, a city known both for its encouragement of fine craftsmanship and the production of items crafted in silver, to attend the Cleveland Institute of Art. After graduating in 1940, Miller divided his time between his own studio and the local firm of Potter and Mellen, where he was given the opportunity to create unique pieces on commission for the store’s upscale clientele. Having this kind of freedom gave Miller’s special genius with silver the space to flower and deepen.

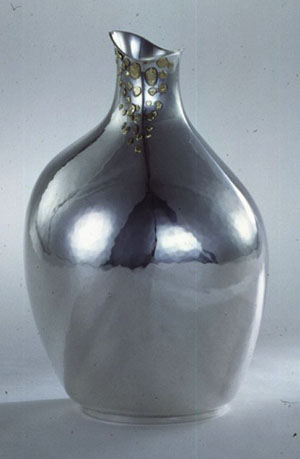

When he worked with silver, he told his mesmerized students at the Cleveland Institute, where he was an illustrious member of the faculty for nearly 30 years (1947–1975), the substance seemed “almost human,” acting “as if it understood you and [was trying] to help.” Indeed, many of Fred Miller’s pieces have the feel of living things.

Besides his “genius for form,” says design historian Alan Rosenberg, who contributed an insightful article about Miller’s work to Silver Magazine (July/August 2007), Miller had a mastery of a revolutionary technique called “stretching.” Introduced to America by the great Swedish silversmith Baron Erik Fleming at the 1948 National Silversmithing Workshop Conference, which Miller attended, stretching was a novel method of thinning a disc of metal into the desired shape—the part of the process known as “raising.” But, whereas the time-honored way was to hammer a thin piece of metal into shape by striking primarily the outside surface of the cup or bowl coming into existence, stretching began with a relatively thick disc and most of the hammering was done on the interior of the emerging form—with the result that, said conference organizer Margaret Craver, “the metal actually flows under the blows of the hammer.”

This method, she argued—and Miller soon discovered first-hand to his eternal delight—was “ideal for irregular shapes, since it permits the smith to vary his form easily as he goes along, combining in a free form a freely flowing design idea.” Elizabth Nutt, a student of Miller’s at the Cleveland Institute, has a vivid memory of his “raising” a large piece “while squatting on top of the studio’s center table, a position that seemed to defy gravity.” In a 1953 article in American Artist, the eminent craftsman Edward Winter credited Miller with “[freeing] design from the conventional round and rectangular shapes,” while developing freer, more contemporary forms. A reviewer writing in Craft Horizons found “an authentic sculptural simplicity” in Miller’s creations.

Miller was to win many major awards. His work was selected for inclusion in 21 consecutive May Shows, the annual juried exhibition (and showcase) of new art and crafts from the region hosted for several decades by the Cleveland Museum of Art. But the museum had no intention of allowing all of Miller’s work to be snapped up by buyers, purchasing several for its own collection.

Exhibitions of Miller’s stunning hollowware—such as the one-person shows mounted in 1961 at New York’s Museum of Contemporary Crafts and in 1968 at the Henry Art Gallery on the University of Washington campus in Seattle—extended his reputation as one of the outstanding artisans of the 20th century. In 1967, Miller and fellow silversmith Jack Schlundt, a former student, bought Potter and Mellen. There Miller oversaw the studio and design operation until his retirement in 1976.

Fellow Arts Prize winner and life partner John Paul Miller, renowned goldsmith, points out, however, that Fred’s own achievements in working with gold and the creation of stunning original jewelry have been overlooked.

—Dennis Dooley

All Photos Courtesy of John Paul Miller