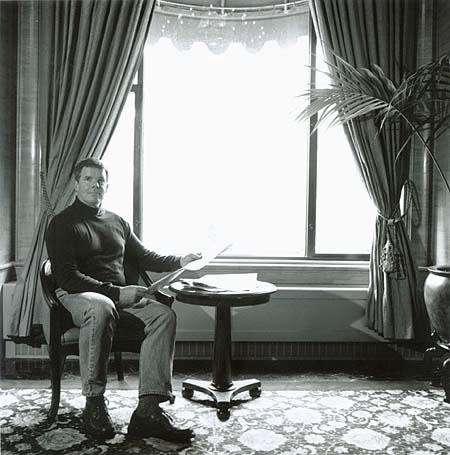

George Bilgere, Poet

2003 CLEVELAND ARTS PRIZE FOR LITERATURE

His extraordinary gift for finding poetry in the everyday

gives the poems of George Bilgere their edge. Whether it is the smell

of corned beef and cabbage that has triggered memories of his mother

cooking out her anger in the kitchen (“Everything was simmering / Just

below the steel lid / Of her smile, as she boiled / The beef into

submission, / Chopped her way / Through the vegetable kingdom / With the

broken-handled knife”) or the sight of his nephew mowing the lawn (“For

the first time, a beast in harness / . . . and I remember / How bitterly I

went into the traces”), Bilgere’s poems are as direct and vivid as

“listening to a friend’s voice over the phone late at night,” said John

Freeman, reviewing the poet’s third collection, The Good Kiss, in The Denver Post.

His extraordinary gift for finding poetry in the everyday

gives the poems of George Bilgere their edge. Whether it is the smell

of corned beef and cabbage that has triggered memories of his mother

cooking out her anger in the kitchen (“Everything was simmering / Just

below the steel lid / Of her smile, as she boiled / The beef into

submission, / Chopped her way / Through the vegetable kingdom / With the

broken-handled knife”) or the sight of his nephew mowing the lawn (“For

the first time, a beast in harness / . . . and I remember / How bitterly I

went into the traces”), Bilgere’s poems are as direct and vivid as

“listening to a friend’s voice over the phone late at night,” said John

Freeman, reviewing the poet’s third collection, The Good Kiss, in The Denver Post.

U.S. poet laureate Billy Collins had the same experience reading the manuscript of The Good Kiss, which had been submitted to a competition he had agreed to judge: the University of Akron Poetry Prize. “He has the most engaging voice,” said Collins. “I didn’t want to stop listening to this voice. The Good Kiss is full of delights and surprises—connections that will widen your eyes—and sudden turns from the humorous into the serious that will throw you against the door. Such effects are the product of a poet who knows how to blend ingeniously the sentimental and the sarcastic . . . the trivial and the desperately serious.”

Collins awarded Bilgere the prize, which included publication by the University of Akron Press in 2002. He also recommended Bilgere for a prestigious Witter Bynner Fellowship, an honor granted only a handful of promising young writers (including Naomi Shihab Nye and Joshua Weiner) by the Witter Bynner Foundation in conjunction with the Library of Congress. In April 2002 Bilgere, who was born in 1951, gave the first of two readings at the Library, followed by a joint reading with Collins in the spring of 2003 at one of New York’s premiere literary venues, the 92nd Street Y. He has also received writing grants from the Society of Midland Authors, the Fulbright Foundation, the Ohio Arts Council and the National Endowment for the Arts.

An

associate professor of English since 1992 at John Carroll University in

University Heights, Ohio, George Bilgere (pronounced Bil-GAIR with a

hard “g”) grew up in Riverside, California. Thanks to an inspiring

teacher, Bilgere realized as an undergraduate at the University of

California, Riverside, that poetry didn’t have to sound like Keats, but

could be written in contemporary English. With The Good Kiss,

he says, he finally discovered a voice that did not have to be

“solemn”—the legacy of the great Howard Nemerov, with whom Bilgere

studied at Washington University in St. Louis before earning a Ph.D. in

contemporary British and American poetry at the University of Denver in

1988. He taught English on TV in Tokyo and spent a year in Bilbao,

Spain, on a Fulbright before settling in Cleveland.

An

associate professor of English since 1992 at John Carroll University in

University Heights, Ohio, George Bilgere (pronounced Bil-GAIR with a

hard “g”) grew up in Riverside, California. Thanks to an inspiring

teacher, Bilgere realized as an undergraduate at the University of

California, Riverside, that poetry didn’t have to sound like Keats, but

could be written in contemporary English. With The Good Kiss,

he says, he finally discovered a voice that did not have to be

“solemn”—the legacy of the great Howard Nemerov, with whom Bilgere

studied at Washington University in St. Louis before earning a Ph.D. in

contemporary British and American poetry at the University of Denver in

1988. He taught English on TV in Tokyo and spent a year in Bilbao,

Spain, on a Fulbright before settling in Cleveland.

Dealing with the pain of a divorce, says George Bilgere, led him to use more “open” language. In the title poem of The Good Kiss an element of rueful humor enters his writing, when he discovers, by candlelight, that the “full moons” of a lover’s breasts are “not hers, exactly.” “Under each of them,” he writes, “was the saddest, / Tenderest little smile of a scar, / Like two sad smiles of apology. / I had them done so he wouldn’t leave, / she said, But in the end he left anyway.”

Bilgere’s poems have appeared in such distinguished journals as Poetry, Ploughshares, The Iowa Review, The Sewanee Review, The Kenyon Review, Shenandoah, Chicago Review, New England Review and Prairie Schooner. His work has been included in a number of anthologies: Best American Poetry (1992 and 1999), American Prose and Poetry in the 20th Century (Cambridge University Press, 2001) and From Both Sides Now: An Anthology of Poetry of the Vietnam War and Its Aftermath (Scribner, 1998).

His first collection, The Going (University of Missouri Press, 1995), won the Devins Award for an outstanding first book of poetry; his second, Big Bang (Copper Beech Press, 1999), was hailed by the Cleveland Plain Dealer as a moving “portrait of mature American manhood and its contradictions.” The Good Kiss was followed by Haywire (Utah State University Press, 2006), winner of the May Swenson Poetry Award, and The White Museum (Autumn House Press, 2009). One of the poems included in this fifth

collection bore the curious title, “Graduates of Western Military.”

Awarded the Pushcart Prize for the best poem published by a small press

the previous year, it was about two men who were classmates at a

military academy in Illinois in the 1930s. One was George’s father, the

other Paul Tibbets, who would gain dubious immortality as the pilot of

the Enola Gay, the B-29 that dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima.

—Dennis Dooley