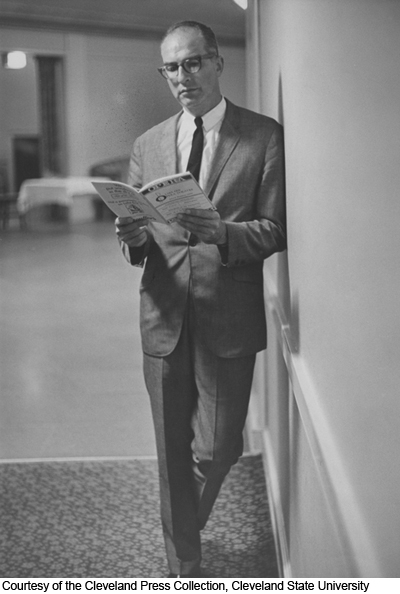

Howard Whittaker, Composer, 1922–1989

1963 CLEVELAND ARTS PRIZE FOR MUSIC

In retrospect, Louis Howard Whittaker might have been honored for any number of things: By the time he retired as director of the Cleveland Music School Settlement (1947-1984), he had extended its music instruction—available to any area child, youth or adult—to additional locations throughout the city, including some 35 social service agencies (ranging from orphanages and hospitals to homes for the disabled, the retarded and the elderly), building enrollment from 400 to 5,000 pupils. Under his innovative leadership, the Music School Settlement (CMSS), the largest institution of its kind in America, pioneered the use of music therapy and then began to teach it. In 1964, the year after he was awarded the Cleveland Arts Prize, Whittaker co-founded the legendary Lake Erie Opera Theater, which presented fully staged operas at Severance Hall with Cleveland Orchestra musicians in the pit. In 1968, he masterminded the first Cleveland Summer Arts Festival, which became a national model.

But when Howard Whittaker was honored in 1963, it was for something else—and this must have touched this sensitive and dedicated man deeply: his achievements as a composer. And they were noteworthy. Born in 1922 in the Cleveland suburb of Lakewood, Whittaker had plunged into music early and with what would become his trademark aplomb: At twelve he marched into the local offices of the Musicians Union to obtain his card, passed the audition and sight-reading tests, and “Skeets," as the older musicians took to calling him, was soon sitting behind a drum set in a dance hall in lakeside Vermilion. He was good enough that both Tommy Dorsey and Benny Goodman offered him a job, and was soon earning enough to put himself through the Cleveland Institute of Music. There he would study music theory with Ward Lewis, conducting with Boris Goldovsky and composition with Herbert Elwell. He graduated in 1943. While stationed at Camp Fannin in Texas, Whittaker composed and led an oratorio and a cantata for male chorus.

In January 1947, while he was still a graduate student at the Oberlin College Conservatory of Music, his Orchestral Fantasy on Hanby Melodies was given its premiere by the Columbus Philharmonic to mark Otterbein College’s centennial. Benjamin Hanby (1833-1867), the Ohio-born composer whose some 80 published songs included the Christmas classic “Up on the Housetop," had been a sophomore at Otterbein when he wrote his other immortal hit, “My Darling Nellie Gray” in 1856. But the ink was scarcely dry on Whittaker’s master’s degree when he was offered, and accepted, the directorship of the Cleveland Music School Settlement.

Given the formidable challenges he now faced as head of the financially struggling Settlement, it might have been understandable—especially in the light of all that he subsequently accomplished—if Whittaker had abandoned composition. (By 1949, the national Guild of Community Music Schools had elected him its president.) But in the years that followed, Whittaker continued to produce pieces of sufficient interest to be performed and recorded by recognized musicians and conductors. In 1953 his setting of the famous "Behold He Cometh with Clouds" passage from the Book of Revelation, commissioned for the 30th anniversary of the award-winning Orpheus Male Chorus, won the Mendelssohn Glee Club Award in a national competition and a performance by that New York ensemble. Robert Shaw recorded it in 1964 for CRI, with the Kulas Choir and tenor soloist Seth McCoy. March 1957 saw the premiere of a four-movement song cycle based on Thomas Wolfe’s novel Of Time and the River and a piano concerto, performed by the Lithuanian pianist Andrius Kuprevicius with the Cleveland Women’s Orchestra; and, the following month, the first performance of a piano sonata, by William Harms, at Carnegie Hall.

—Dennis Dooley