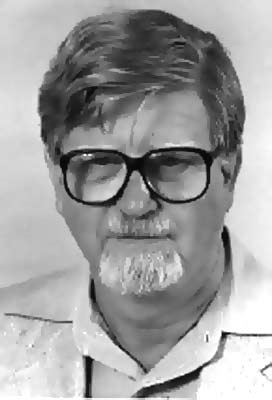

James Waters, Composer, 1930 - 1996

1993 CLEVELAND ARTS PRIZE FOR MUSIC

The fact that James Waters was born in Kyoto, Japan, in 1930, the child of Methodist ministers, may or may not explain the composer’s

lifelong preoccupation with the heartbreaking toll of war on human

beings. When listening to his memorable settings of Stephen Crane’s ironic song cycle War is Kind and four poems of Walt Whitman’s from Drum-Taps

for mezzo-soprano solo, chorus and wind ensemble, it is easy to picture

15-year-old James glued to radio bulletins about the desperate

hand-to-hand fighting on Iwo Jima and the obliteration of Hiroshima and

Nagasaki.

The fact that James Waters was born in Kyoto, Japan, in 1930, the child of Methodist ministers, may or may not explain the composer’s

lifelong preoccupation with the heartbreaking toll of war on human

beings. When listening to his memorable settings of Stephen Crane’s ironic song cycle War is Kind and four poems of Walt Whitman’s from Drum-Taps

for mezzo-soprano solo, chorus and wind ensemble, it is easy to picture

15-year-old James glued to radio bulletins about the desperate

hand-to-hand fighting on Iwo Jima and the obliteration of Hiroshima and

Nagasaki.

His family had moved to America when he was two and during his teenage years lived in Arlington, Virginia, just across the Potomac from Washington, D.C. Jame’s father translated intercepted Japanese communications for the FBI. Young James’s world was already full of music. Having started out on the piano, because his legs were too short to reach the organ’s pedals, he now occasionally accompanied the church choir.

At Westminster Choir College in Princeton, New Jersey, where he earned both his bachelor’s and master’s degrees, Waters majored in organ and conducting, but he was finding increasing satisfaction in composing music. The Ph.D. dissertation composition he wrote under Bernard Rogers at the Eastman School of Music in 1966, a setting of Three Holy Sonnets of John Donne, won the Louis Lane Prize and was conducted by Howard Hanson on the Festival of American Music. But Waters soon found himself growing restless with the constrictions of the 12-tone system, though, perhaps feeling the old church organist’s urge to connect with the secret hearts of his congregation, he had managed to bring a distinctive lyricism to his composition. His Lyric Piece for violin, clarinet and piano (1971), which began as a 12-tone row but grew into something quite unexpected, has been performed at least 10 times around the U.S.

Waters’s setting in the late 1970s of five anti-war poems by Stephen Crane, author of the classic Civil War novel The Red Badge of Courage (and also the son of a Methodist minister), was downright audience-friendly, harmonically speaking. But if the composer, who now saw himself as an exponent of German romanticism, confessed that he thought of each of these songs as being in a certain key, his writing was edgy and unpredictable. “Fitful, restless chromatic configurations,” noted Plain Dealer critic Robert Finn, underlay Crane’s “quick stream of men pouring ceaselessly,” and a series of disjointed thirds were used to evoke “a man with a tongue of wood who essayed to sing”; but when the singer at last finds a sympathetic listener, Finn observed, “the same chords become lyrical, a nice touch.”

When he came upon the heartbreaking verses Whitman had written about tending wounded soldiers in an army hospital during the Civil War (“Who are you my sweet boy with cheeks yet blooming?”) in the mid-1980s, Waters felt compelled to set them to music. The second movement of Four Visions of War, an impossible march with five beats instead of the usual four (“So strong you thump O terrible drums”), captures the all-trampling juggernaut of war, while Waters’s tender setting of the third poem evokes the yellow-ivory features of a dying soldier that become for Whitman the face of Christ (“and here again he lies”). The American Record Guide called Four Visions a “powerful and dramatic work . . . dark and turbulent.” “This 21-minute work alone,” wrote Fanfare’s Robert McColley, “is worth the cost of the disc.”

Awarded the Cleveland Arts Prize in 1993 for his excellence as a composer, Waters was also a distinguished educator who taught theory and composition at Westminster Choir College from 1957 to 1968 and from 1968 to 1996 at Kent State University, from which he retired as professor emeritus. An accomplished pianist, he is a past president of the Cleveland Composers Guild.

James Waters’s compositions for voice, keyboard, orchestra and various chamber ensembles (published by G. Schirmer, Carl Fischer, Galaxy Music Corporation and Ludwig Music Publishing Corporation) have been widely performed by such forces as the Princeton Chamber Orchestra, the Aeolian Chamber Players and the 20th Century Consort. Distinguished interpreters such as Janet Alcorn, at Washington D.C.’s Kennedy Center, Janice Harsanyi, Daune Mahy and Mary Sue Hyatt have performed his songs, which include cycles on poems by Louise Bogan and Emily Dickinson. His viola concerto was given its world premiere by Marcia Ferritto and the Cleveland Chamber Symphony under the baton of Edwin London in 1988.

—Dennis Dooley

For more about James Waters visit my.en.com/~jaquick/jwbio.html