Judith Salomon, Ceramist 1990 CLEVELAND ARTS PRIZE FOR VISUAL ARTS

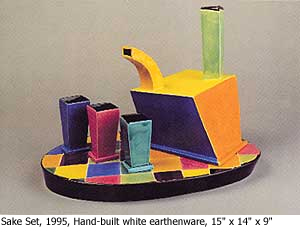

Salomon, a native of Rhode Island, says she had been drawn to the decorative arts ever since she can remember. Her father was a soil chemist at the University of Rhode Island, and her exposure to European culture and architecture during his sabbaticals in England and Portugal further fueled her imagination. When she took her first throwing class, at age 15, she knew she had discovered the vessels that could hold her creative ideas. Salomon went on to earn a B.F.A. from the Rochester Institute of Technology (1975) and an M.F.A. from the New York State College of Ceramics at Alfred University (1977). Following graduation, she was named associate professor at the Cleveland Institute of Art. Cleveland—and the institute—have been home ever since. Her artwork, inspired by her love of architecture, is an exploration of what she calls “containers and containment. How insides and outsides work together.” She builds each piece by hand, creating work that suggests sculpture: Although all of her pieces “hold something,” they are clearly designed for form over function. Salomon’s early work, mostly plates and bowls, had a distinctive look: brightly colored geometric shapes floated on fields of white. Over time, she experimented with new shapes, bolder lines, warmer tones, more contrast and one-color pieces, including, most recently, all-white ones. She began mixing matte and high-gloss glazes, sometimes in the same piece. In her hands, familiar objects, such as teacups and vases, held playful surprises.

In the decade that followed that serendipitous break, she exhibited her work in 24 shows. Her reach would expand to Canada, Taiwan, New Zealand, England and Wales. Her collectors included the Cleveland Museum of Art, London’s Victoria and Albert Museum, and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Many would argue that Salomon’s talent in the studio is matched by her skill in the classroom. If she gets high marks from her students, she says, it’s because she believes she learns as much from their questions as they do from her teaching. She and they share in the creative process, growing side-by-side, as artists. She is equally concerned about her students’ personal growth, giving them a secure place to “find out who they're going to be”—and what they might do with their art. Working with colleague William Brouillard, she guides them through the art world, helping them find residencies and graduate programs. She has also lent support to emerging artists at SPACES, Cleveland’s alternative gallery space, where for many years she served as trustee.

In 1994, Salomon and her husband, Jerome Weiss, added “Mom” to her growing list of job descriptions. Since then, her work pace has slowed a bit, but the artist continues to do what she loves: exploring the aesthetic of clay. —Faye Sholiton For more on the artist visit www.cia.edu |

Judith Salomon

Judith Salomon  Salomon’s

work came to national prominence during her third or fourth year in

Cleveland. Recalling a professor’s advice to “make sure your work

leaves the studio,” she donated a piece for auction at the Archie Bray

Foundation in Helena, Montana, where she was in summer residency. The

high bidder was Garth Clark, a dealer who would show her work in his

Los Angeles and New York galleries for the next 12 years. He would also

include her in his books, American Potters Today (1986) and American Ceramics 1876 to Present (1987).

Salomon’s

work came to national prominence during her third or fourth year in

Cleveland. Recalling a professor’s advice to “make sure your work

leaves the studio,” she donated a piece for auction at the Archie Bray

Foundation in Helena, Montana, where she was in summer residency. The

high bidder was Garth Clark, a dealer who would show her work in his

Los Angeles and New York galleries for the next 12 years. He would also

include her in his books, American Potters Today (1986) and American Ceramics 1876 to Present (1987). In

addition to working fulltime at the institute, Salomon maintains a

studio in Cleveland's eclectic Tremont neighborhood, which borders the

city’s industrial heart. Its mix of old and renovated architecture

continues to inspire new work, including major commissions from noted

Cleveland collector

In

addition to working fulltime at the institute, Salomon maintains a

studio in Cleveland's eclectic Tremont neighborhood, which borders the

city’s industrial heart. Its mix of old and renovated architecture

continues to inspire new work, including major commissions from noted

Cleveland collector