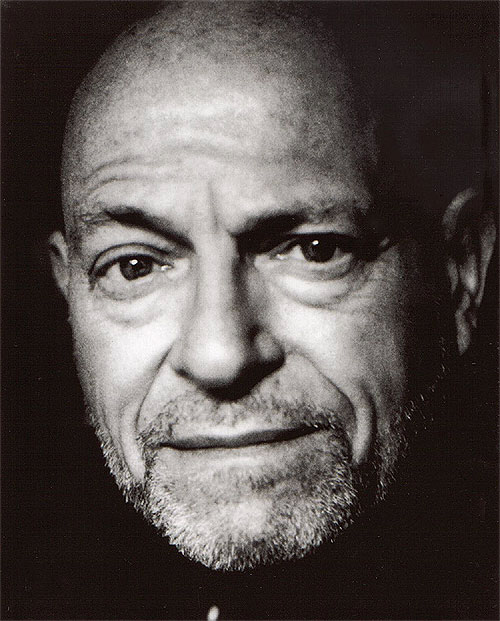

Richard Howard, Poet

1974 CLEVELAND ARTS PRIZE FOR LITERATURE

On October 24, 1929, when

Richard Howard when Richard Howard was just 11 days old, the stock

market crashed. Whether the little boy sensed an anxious mood in the

air of Cleveland as he learned to walk and talk cannot of course be

known, but the times clearly called for an extraordinary gesture. By

the age of four he resolved to be a poet. More than 30 years would

pass before his first book of poems, Quantities, would be published. It would be warmly received by the critics, impressed by its technical brilliance.

On October 24, 1929, when

Richard Howard when Richard Howard was just 11 days old, the stock

market crashed. Whether the little boy sensed an anxious mood in the

air of Cleveland as he learned to walk and talk cannot of course be

known, but the times clearly called for an extraordinary gesture. By

the age of four he resolved to be a poet. More than 30 years would

pass before his first book of poems, Quantities, would be published. It would be warmly received by the critics, impressed by its technical brilliance.

As a child, he seems to have spent a great deal of time listening to what was being said all around him in those years of extraordinary societal self reflection. His second collection, The Damages (1967), established Howard’s unique gift for conjuring other voices—especially historical voices. His third book, Untitled Subjects, in which he reanimates the voices of Tennyson, Ruskin, Gladstone, the novelist Wilkie Collins and other eminent figures of an earlier age, to stunning effect, won the 1970 Pulitzer Prize.

More than a dozen more critically acclaimed collections of Howard’s poetry would follow over the next four decades, along with two books of criticism, Alone with America: Essays on the Art of Poetry in the United States Since 1950 (1969) and Preferences, which appeared in 1974, the year he was awarded the Cleveland Arts Prize. For the latter book, Howard had asked 51 living poets to choose one of their own poems and an older poem by someone else that it reminded them of. Howard contributed a brief reflection on the pair. This ingenious experiment was hailed as “a valuable contribution to literary criticism.”

The same year, Howard’s own fifth collection, Two-Part Inventions, cemented his position as master of the dramatic monologue. He has a way of getting into the minds of long-dead writers and artists like Rodin, Proust, Kafka, Yeats, Liszt—and Robert Browning, whose famous dramatic monologues, particularly “My Last Duchess,” are clearly the inspiration for Howard’s own work. In other poems, he talks directly to his subjects or meditates on the lives of forgotten authors.

Howard has also won acclaim for his translations of more than 150 books by some of France’s leading writers (including Camus, Gide, Robbe-Grillet, Andre Breton, Roland Barthes, Stendhal and Simone de Beauvoir), a love he developed as a graduate student at the Sorbonne in the early 1950s following his graduation from Columbia University. He received the PEN Translation Prize in 1976 for his translation of the Rumanian writer E. M. Cioran’s A Short History of Decay; an American Book Award in 1984 for Baudelaire’s Les Fleurs du Mal; the PEN American Center medal for translation (1986); the France-America Foundation Award (1987); and the Ordre National de Mérite from the French government—as well as, for his own writing, the Levinson Prize, the Harriet Monroe Memorial Prize, and the National Institute of Arts and Letters Literary Award.

The publication in 2005 of Inner Voices: Selected Poems 1963-2003, which brought together the most beloved and provocative of Howard’s verse, was greeted almost universally with glowing praise. Harold Bloom proclaimed him “Browning’s authentic heir.” “While he modernly dispenses with rhyme and meter, Howard shapes his poems by other means,” wrote Ray Olson in Booklist, “retaining the rhythms and swing of intelligent talk.” Publishers Weekly assured readers that the book included “Howard’s anthology hits, among them ‘Nicholas of Mardruz [to His Master Ferdinand, Count of Tyrol, 1565]’ (a biting response to Browning) and ‘Infirmities,’ in which the aged Walt Whitman critiques the closeted Bram Stoker.”

Howard, who is openly gay, admits to a lifelong fascination with the gay experience of life, which became increasingly explicit in his later books. His 12fth and last collection to appear before the selected poems, Talking Cures (2002), includes, besides the ailing Whitman’s words to the author of Dracula, an irreverent series of nine satirical poems grouped under the title “Phallacies” in which Marilyn Monroe appears. Art collector Peggy Guggenheim, the poet John Milton and Alice Liddell (the original of Alice in Wonderland) looking back in old age also pop up, with memorable results, in Howard’s later books.

During his years of teaching at Columbia, the University of Houston and (briefly) Yale, as chancellor of the Academy of American Poets, and poetry editor of The Western Humanities Review and The Paris Review, Richard Howard has had an additional impact on the landscape of American poetry that is difficult to measure. He was invited to edit the Library of America’s compendium of The Best American Poetry (1995) along with a selection of Henry James’s travel writing, to which he contributed a thoughtful introductory essay. A selection of Howard’s own prose writings from 1965 to 2003, titled Paper Trail, was published by Farrar Straus Giroux in 2005 in tandem with his selected poems.

—Dennis Dooley

RUSKIN ON THE DEATH OF TURNER

[In a letter to his father, then art critic John Ruskin reflects on the recent death of the much maligned painter

J. M. W. Turner:]

. . . I do not feel any

Romance in Venice!

Here is no “abiding city,” here is but

A heap of ruins trodden underfoot

By such men as Ezekiel

Angrily describes,

Here are lonely and stagnant canals, bordered

For the most part by blank walls of gardens

(Now waste ground) or by patches

Of mud, with decayed

Black gondolas lying keel-upmost, sinking

Gradually into the putrid soil.

To give Turner’s joy of this

Place would not take ten

Days of study, father, or of residence:

It is more than joy that must be the great

Fact I would teach. I am not sure,

Even, that joy is

A fact. I am certain only of the strong

Instinct in me (I cannot reason this)

To draw, delimit the things

I love—oh not for

Reputation or the good of others or

My own advantage, but a sort of need,

Like that for water and food.

I should like to draw

All Saint Mark’s, stone by stone, and all this city,

Oppressive and choked with slime as it is

(Effie of course declares, each

Day, that we must leave:

A woman cannot help having no heart, but

That is hardly a reason she should have

No manners), yes, to eat it

All into my mind—

Touch by touch. I have been reading Paradise

Regained lately, father. It seems to me

A parallel to Turner’s

Last pictures—the mind

Failing altogether, yet with intervals

And such returns of power! “Thereupon

Satan, bowing low his gray

Dissimulation,

Disappeared.” Now he is gone, my dark angel,

And I never had such a conception

Of the way I must mourn—not

What I lose, now, but

What I have lost, until now. Yet there is more

Pain knowing that I must forget it all,

That in a year I shall have

No more awareness

Of his loss than of that fair landscape I saw,

Waking, the morning your letter arrived,

No more left about me than

A fading pigment.

All the present glory, like the present pain,

Is no use to me; it hurts me rather

From my fear of leaving it,

Of losing it, yet

I know that were I to stay here, it would soon

Cease being glory to me—that it has

Ceased, already, to produce

The impression and

The delight. I can bear only the first days

At a place, when all the dread of losing

Is lost in the delirium

Of its possession.

I daresay love is very well when it does not

Mean leaving behind, as it does always,

Somehow, with me. I have not

The heart for more now,

Father, though I thank you and Mother for all

The comfort of your words. They bring me,

With his loss, to what I said

Once, the lines on this

Place you will know: “The shore lies naked under

The night, pathless, comfortless and infirm

In dark languor, still except

Where salt runlets plash

Into tideless pools, or seabirds flit from their

Margins with a questioning cry.” The light

Is gone from the waters with

My fallen angel,

Gone now as all must go. Your loving son,

--Excerpt from "1851: A Message to Denmark Hill," Inner Voices: Selected Poems, 1963-2003 (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2004)