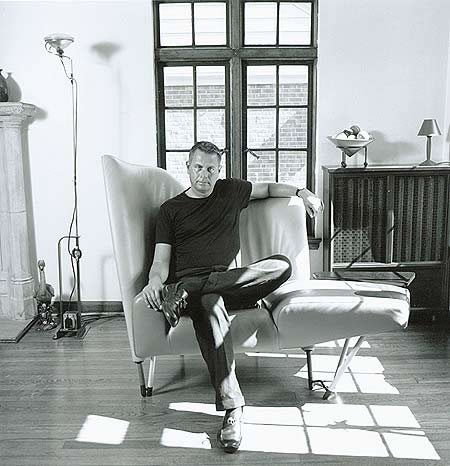

Vince Leskosky, A.I.A., Architect

2003 CLEVELAND ARTS PRIZE FOR ARCHITECTURE

Vince Leskosky brings an artist’s eye

to the challenge of designing a building. His aim is to create a

satisfying composition in which all the parts work together, down to

the smallest detail. His “canvas” includes the building's interior, to

which he always devotes meticulous attention. The client’s desires and

the building’s specific function are, of course, where his design

concepts begin.

Vince Leskosky brings an artist’s eye

to the challenge of designing a building. His aim is to create a

satisfying composition in which all the parts work together, down to

the smallest detail. His “canvas” includes the building's interior, to

which he always devotes meticulous attention. The client’s desires and

the building’s specific function are, of course, where his design

concepts begin.

An avid painter and sculptor whose work has been exhibited at New York’s Cooper-Hewitt Museum, the Cleveland Museum of Art’s May Shows, the Cleveland Center for Contemporary Art and SPACES Gallery, among other venues, Leskosky goes on to consider such formal issues as the organization of foreground and background, depth and openness, the relation of interior to exterior, shapes and colors, as well as the textures and the fabrics chosen to complete his spaces. (In fact, he received an award from the Institute of Business Designers and the Cleveland chapter of the American Institute of Architects [AIA] for the interior design of the Amethyst Grille in Shaker Heights.) Leskosky also thinks deeply about how his design will make its users feel and how it might enhance their activities and interactions.

A kidney dialysis center becomes a light-filled, reassuring and healing environment that uses tall clerestory windows to connect patients—who must remain in treatment for many hours—with the outside world: clouds moving overhead, birds circling, even rain. Instead of the vinyl-covered furniture of the sort typically found in clinics and fast-food restaurants, warm, comfortable fabrics and interesting textures were chosen for the appointments. Instead of cold tile floors, Leskosky opted for a germ-free plastic laminate that looks like wood, while jettisoning institutional pink and pale blue-green in favor of stronger or more saturated colors that stir the spirit and massage the senses.

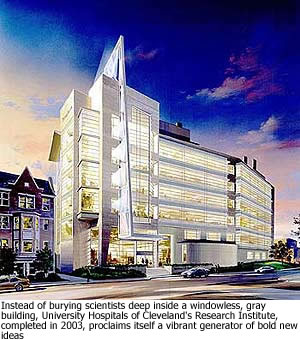

Commissioned to design a research facility for University Hospitals of Cleveland, Leskosky interviewed its future occupants, asking researchers such practical questions as how they would work at their benches, and with what kind of equipment. Angles, textures and light were employed to mitigate stress, and workspaces were configured to maximize the potential for interaction, while research areas were made flexible to respond cost-effectively to constantly changing pursuits.

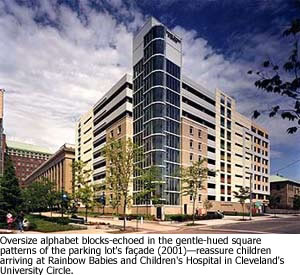

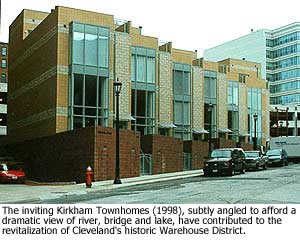

The satisfying “whole,” for Leskosky, includes a building’s relationship to its setting. Hemmed in on one side by an 18-story apartment building and a parking garage on another, the Kirkham Townhouses he designed for Cleveland’s Warehouse District were angled to face a spectacular view encompassing the Cuyahoga River, the Main Avenue Bridge and Lake Erie. The presence of so many windows aimed down at the sidewalk helps make the neighborhood a safer place to live, Plain Dealer architecture critic Steve Litt noted, and raised masonry terraces create a semi-private zone. Finally, the squash-colored tile Leskosky used for the fašade gives them “a visual warmth and fine-grained detail sympathetic to the district’s 19th-century roots,” while decorative bands of split-face concrete blocks “emulate early 20th-century commercial architecture.”

As a principal and senior project designer at van Dijk Westlake Reed Leskosky with 22 years of experience, Leskosky brings a wealth of knowledge to his projects, which have included everything from a new facility for Banner Health System’s Thunderbird Samaritan Medical Center in Glendale, Arizona, to the Ohio Motorists Association’s corporate headquarters on a bluff overlooking I-77 and I-480, one of the busiest intersections in the state.

Although he took courses in art and photography at Youngstown State University while still a student at Boardman High School, the Youngstown native found himself drawn more and more to his first love as a boy, architecture. He went on to pursue a master’s in architecture at Kent State University, where he served as teaching assistant to Thom Stauffer, winner of the 2002 Cleveland Arts Prize for Architecture. (Leskosky himself would teach evening classes in architectural design theory at KSU from 1982 to 2000.) Upon his graduation in 1980, Leskosky was brought into a new firm being established by Stauffer and Neil Guda, who had directed Leskosky’s thesis. Leskosky joined van Dijk Pace Westlake in 1982.

Perhaps Leskosky’s most unusual assignment was designing the prototype for a chain of 125 truck stops spread across 36 states being newly built or converted by Travel Centers of America to serve both professional drivers and “four-wheelers” (truckers’ slang for regular motorists). The open, welcoming feel of the prototype-

which evokes the family-friendly Big Boys and original McDonald’s of the post World War II and early ’50s era—is

achieved with bold shapes, bright colors, neon signage, a fašade of

glass and ribbed aluminum, and huge striped awnings, jazzy elements

that impart what has been called “the wow factor.” Inside: a

comfortable, natural-light-filled restaurant, shopping center, massage

rooms and marble shower stalls (for the long haulers) modeled after

those at the Ritz-Carlton. The New York Times pronounced

Leskosky’s imaginative design the first “re-imagining” of an American

institution, the truck stop, since it was introduced 80-

some years ago.

—Dennis Dooley