William McVey, Sculptor, 1904–1995

1964 CLEVELAND ARTS PRIZE FOR VISUAL ARTS

Few artists have left as many monuments on the American landscape as sculptor William Mozart McVey.

His nine-foot bronze Winston Churchill (1966) greets visitors to the

British Embassy in Washington, D.C. Not far away, six statues sculpted

by McVey between 1967 and 1974 can be found in the porch and crypt of

the National Cathedral. His memorials to Davey Crockett, Jim Bowie and

the heroes of the Alamo were the centerpieces of Texas’s centennial in

1936. His stone and cast bronze animals that reside in many of the

nation’s zoos are as beloved as any of the caged ones.

Few artists have left as many monuments on the American landscape as sculptor William Mozart McVey.

His nine-foot bronze Winston Churchill (1966) greets visitors to the

British Embassy in Washington, D.C. Not far away, six statues sculpted

by McVey between 1967 and 1974 can be found in the porch and crypt of

the National Cathedral. His memorials to Davey Crockett, Jim Bowie and

the heroes of the Alamo were the centerpieces of Texas’s centennial in

1936. His stone and cast bronze animals that reside in many of the

nation’s zoos are as beloved as any of the caged ones.

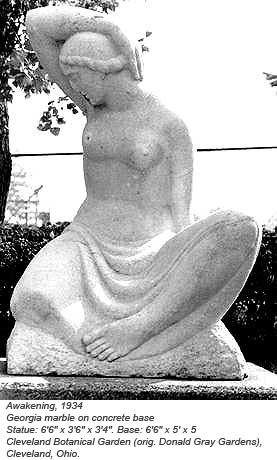

But it was in northeastern Ohio that McVey left the greatest body of his work. Among his 48 pieces of public sculpture: the 16-foot Long Road aluminum wall relief (1962) for the now-defunct Jewish Community Center in Cleveland Heights; Man Helping Man (1974), on which the sculptor is working in the photograph at the right and which became a logo of the Cleveland Clinic Foundation; the seven-foot bronze Jesse Owens (1982) on Lakeside Avenue in Cleveland; and the bronze monument to his own wire-haired terrier, McDog (1985), at the Cleveland Botanical Garden.

McVey, who was born in Boston, moved to Cleveland as a teenager and graduated from Shaw High School in 1922. He enrolled at the Cleveland School of Art (which later became the Cleveland Institute of Art), but soon seized another opportunity that took advantage of his athletic, six-foot-4-inch frame. He played football for Rice University’s Coach John Heisman, on a full scholarship. After three years (and several nose realignments) he returned to Cleveland to complete his degree.

He went next to Paris for three years to study sculpture, learning from such luminaries as Charles Despiau, who had worked with Rodin. Although he was exposed to modernism in the City of Light, McVey preferred a more natural style for his own work. Early McVey sculpture tended to be honest, expressive and simple, inspired by primitive art. A skilled illustrator, he soon mastered representational sculpture. Later, he would embrace modern styles, as well as the humor that would characterize much of his work.

While in Paris, he supported himself by guiding Americans through the Louvre, a task made simple because, as he later recounted, Yanks’ interest generally waned after seeing the Venus de Milo, Winged Victory and Mona Lisa.

When he returned to Cleveland in 1932, he received a Works Progress Administration commission to create a sculpture for the new Museum of Natural History. From a six-ton block of limestone emerged a four-ton grizzly bear, affectionately known as “Bruno,” who has survived more than seven decades of children’s affection. It was also in 1932 that McVey married potter Leza Marie Sullivan and landed his first teaching job, at the Cleveland Museum of Art.

From 1935 through 1953, McVey taught at the University of Texas and at Michigan’s Cranbrook Academy of Art. He interrupted his art career for four years during World War II to train combat troops in plane and ship identification. He returned to Cleveland in 1953, this time, for good.

His

achievements in sculpture were surpassed only by his achievements as a

teacher at the Cleveland Institute of Art. Many artists call him their

spiritual father, including John Clague,

who as a fourth-year painting student signed up for McVey’s sculpture

course in the fall of 1953. During the first class, McVey articulated

his definition of the scope and limitations of sculpture, Clague

recalls. “It was a definition broader, richer and more expansive than

anything I had ever heard before.”

His

achievements in sculpture were surpassed only by his achievements as a

teacher at the Cleveland Institute of Art. Many artists call him their

spiritual father, including John Clague,

who as a fourth-year painting student signed up for McVey’s sculpture

course in the fall of 1953. During the first class, McVey articulated

his definition of the scope and limitations of sculpture, Clague

recalls. “It was a definition broader, richer and more expansive than

anything I had ever heard before.”

McVey next spoke of art as the reflection of the nature of the artist’s character, “simultaneously defining the grandest possibilities of sculpture as art form, and the grandest possibilities of sculptor as human being.” By the time Clague finished the course, McVey had changed his major to sculpture.

Bill McVey, as professor and artist, aimed for accessibility. His goal, he said, was “the presentation of the sculptural idea in a form acceptable and meaningful to the intelligent layman, without sacrificing quality.” He succeeded on both counts. The Cleveland Museum of Art began collecting his work in 1932. In time McVey’s work was represented in collections from the Smithsonian to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. He was invited into the prestigious 300-member National Academy of Design and became a fellow of the National Sculpture Society. His Bauhaus-style studio/home in Pepper Pike was yet another monument to this one-of-a-kind artist.

For

those who knew him, however, Bill McVey’s greatest legacy was the gift of

laughter, which permeated every aspect of his life and art. Churchill’s

bronze cigar sat in an ashtray; a terra cotta bird struggled to hatch

from a ceramic egg McVey had fashioned; and a handmade sign over the

door read:

BE ALERT. WE NEED MORE LERTS.

Click here to see more of McVey's work.