Robert A. Little, FAIA, Architect, 1919–2005

1965 CLEVELAND ARTS PRIZE FOR ARCHITECTURE

The choice of Robert Andrews Little to receive the Cleveland Arts Prize in 1965 was a recognition not only

of the excellence of his design work, but of his influential role in

introducing the language and philosophy of architectural modernism to

the city. He was also ahead of his time in designing homes with

energy-saving features that were respectful of the environment and

enabled their owners to live in harmony with nature. Bob Little

fervently believed architecture could change people’s lives, and he was

passionate in his conviction that good design should be available not

just to the affluent, but to every American.

The choice of Robert Andrews Little to receive the Cleveland Arts Prize in 1965 was a recognition not only

of the excellence of his design work, but of his influential role in

introducing the language and philosophy of architectural modernism to

the city. He was also ahead of his time in designing homes with

energy-saving features that were respectful of the environment and

enabled their owners to live in harmony with nature. Bob Little

fervently believed architecture could change people’s lives, and he was

passionate in his conviction that good design should be available not

just to the affluent, but to every American.

When the young Boston-born architect (a direct descendant of Paul Revere) arrived in Cleveland in 1947, he found a community whose taste in buildings, including private homes, still reflected the turn-of-the-century Beaux Arts school of design that originated in Paris. When he began teaching courses at Western Reserve University’s school of architecture, he discovered that even the next generation was being inculcated with these noble, but backward-looking principles. Having studied with Marcel Breuer and Walter Gropius, the founder of the influential Bauhaus school of design, at Harvard University, Little (Class of 1937; M.A., 1939) saw architecture in a different light. It should meet the needs and reflect the spirit, he believed, of contemporary living. As one of the first architects in Cleveland to apply the principles of the Bauhaus and the new International Style, Little quickly became the hero of the young architecture students in town.

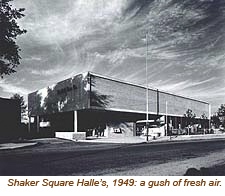

His first local commission, designing the second suburban branch of Cleveland’s Halle’s department store on Shaker Square between the Colony Theater and the rapid transit stop, was a gush of fresh air. Constructed in 1949, it was a handsome, “20th-century building . . . of glass and brick, surrounded by trees and flowers,” he would remember, without “a single dovecote concealing a burglar alarm, and not one green shutter nailed open beside an arched window nailed shut.” The design won both the Cleveland Chamber of Commerce Award for Commercial Building and the Architects’ Society of Ohio Medal for Commercial Building.

However,

Bob Little’s greatest passion was for the creation of homes, indeed

homes of a very special nature. In 1948 he was hired to design the

Timken residence in Canton, Ohio. But Little was also determined to

make good design affordable to the young families flocking to the

suburbs in the years following World War II. New homes were going up

everywhere, but they were for the most part mass-produced, poorly

designed “little boxes made of ticky-tacky” that “all look just the

same,” as a satirical song of the period mocked.

However,

Bob Little’s greatest passion was for the creation of homes, indeed

homes of a very special nature. In 1948 he was hired to design the

Timken residence in Canton, Ohio. But Little was also determined to

make good design affordable to the young families flocking to the

suburbs in the years following World War II. New homes were going up

everywhere, but they were for the most part mass-produced, poorly

designed “little boxes made of ticky-tacky” that “all look just the

same,” as a satirical song of the period mocked.

Design,

Little had decided in 1935, while considering the plight of long-term

patients in a hospital in Finland, “must be based not on precedent,

tradition, style, economics, statistics; but simply and totally on

people. The people who will use it, see it, feel it, build it, pay for

it, be inspired by it. Later, I discovered that this same rule applied

to all valid and original architecture of the past—the Greek temple,

the Gothic cathedral, the Colonial church.” And so he began each new

assignment afresh, with detailed diagrams or “cartoons” of the owners’

living habits and activities, sketching freehand with a pencil as they

looked on.

Design,

Little had decided in 1935, while considering the plight of long-term

patients in a hospital in Finland, “must be based not on precedent,

tradition, style, economics, statistics; but simply and totally on

people. The people who will use it, see it, feel it, build it, pay for

it, be inspired by it. Later, I discovered that this same rule applied

to all valid and original architecture of the past—the Greek temple,

the Gothic cathedral, the Colonial church.” And so he began each new

assignment afresh, with detailed diagrams or “cartoons” of the owners’

living habits and activities, sketching freehand with a pencil as they

looked on.

Moving beyond the accepted convention of rooms as a series of enclosed boxes, he created innovative configurations of airy, but highly functional, spaces that flowed into one another with minimal barriers to sight or freedom of movement. While other architects were being carried away by the ability of post-war technology to produce, for example, towering sheets of distortion-free glass, Little noticed that, after dark, these huge windows became black mirrors that intimidated the residents and made them feel small and cold and vulnerable. “Bob had a feel for human scale that was uncommon in modernist architects,” recalls his colleague Robert Blatchford. While many of them seemed obsessed with verticality, Little thought in all three dimensions, about what would enhance a family’s quality of life. Perhaps the fact that he himself was constantly drawing—in his diaries, on correspondence, on almost any clean, flat surface that came to hand—contributed to the fluidity and artfulness that characterized his architectural designs. (His lifetime love affair with watercolors gave birth to hundreds of landscape and travel paintings that were frequently exhibited.)

Little

invented (and patented) a pre-computer design tool called Solux that

allowed him to trace the path of the sun over a cardboard model

mechanically, instead of having to use laborious mathematical

calculations. This enabled him to design windows that maximized

available winter sunlight to help heat the interior of the house and

eaves that helped keep the interior cool during the summer. He also

made use of the Venturi effect, achieved by guiding breezes over

earthen berms, to cool houses naturally, and put portions of his houses

below ground to capture underground heat, which remains at a constant

50 degrees.

Little

invented (and patented) a pre-computer design tool called Solux that

allowed him to trace the path of the sun over a cardboard model

mechanically, instead of having to use laborious mathematical

calculations. This enabled him to design windows that maximized

available winter sunlight to help heat the interior of the house and

eaves that helped keep the interior cool during the summer. He also

made use of the Venturi effect, achieved by guiding breezes over

earthen berms, to cool houses naturally, and put portions of his houses

below ground to capture underground heat, which remains at a constant

50 degrees.

Looking for ways to cut costs associated with traditional wood-frame construction, he created, on the roof of Kauffman’s Department Store in Pittsburgh, a 1,000-square-foot prototype all-steel home—an idea whose time, it turned out, had not yet come, even in Pittsburgh. In the late 1950s, Little was retained by Westinghouse Corporation to design a prototype all-electric home (then a novelty) suitable for the Midwest and to hire and supervise a team of architects across the U.S. to design other all-electric homes that would serve different climates. At the invitation of Better Homes & Gardens magazine, he designed an affordable home that was published with a variety of options allowing for individualization. Sixty versions of this design were eventually built around the country.

Little’s

crowning achievement was a visionary development in Pepper Pike, Ohio,

called Pepper Ridge, the first planned street of truly modern houses in

the state, built for himself and a small circle of friends. Departing

dramatically from the cookie-cutter approach of the era with its

prescribed setbacks and fixed orientations, Little positioned each home

with respect for the landscape and to take advantage of the best views.

The lots were of different sizes, the setbacks varied, and the layouts

customized to meet each household’s needs. (The home attached to a

barn-turned-studio he created for Cleveland sculptor William McVey won an award from Progressive Architecture.)

Houses were built into hillsides; small lakes were created to slow the

runoff. Little even designed the signage and mailboxes for the street.

His undersized, meandering road added to the community's feeling of

comfort and intimacy.

Little’s

crowning achievement was a visionary development in Pepper Pike, Ohio,

called Pepper Ridge, the first planned street of truly modern houses in

the state, built for himself and a small circle of friends. Departing

dramatically from the cookie-cutter approach of the era with its

prescribed setbacks and fixed orientations, Little positioned each home

with respect for the landscape and to take advantage of the best views.

The lots were of different sizes, the setbacks varied, and the layouts

customized to meet each household’s needs. (The home attached to a

barn-turned-studio he created for Cleveland sculptor William McVey won an award from Progressive Architecture.)

Houses were built into hillsides; small lakes were created to slow the

runoff. Little even designed the signage and mailboxes for the street.

His undersized, meandering road added to the community's feeling of

comfort and intimacy.

Convincing corporate clients to abandon time-honored architectural traditions was often another matter. Little, whose commitment to good design was fierce, was known to walk away from clients who didn’t appreciate modern architecture. In the face of raised eyebrows and decided frowns among his establishment clients in the late 1940s, he hired young Jewish and African-American architects and engineers. But his reputation continued to grow. In 1969, Little & Associates merged with Dalton·Dalton Associates. By the time he retired as a principal of Dalton·Dalton·Little·Newport in the late 1970s, Bob Little had completed such important commissions as the Community Health Foundation facility in University Circle (which was later occupied by Kaiser Permanente and is now the Community Dialysis Center), Jane Addams High School, the Case Institute of Technology dorms along Cedar Hill, several buildings for Hawken School’s upper school campus in Gates Mills, the Cleveland Municipal School District’s spherical Supplementary Education Center (and planetarium) on Lakeside Avenue, the corporate headquarters of the Revco (now CVS) drugstore chain in Twinsburg and the United States Air Force Museum in Dayton. The twin towers he designed for Cleveland’s Metro General Hospital (now MetroHealth Medical Center) located the nurses’ station at the center of each floor so all the patients’ rooms were constantly in sight—then a unique innovation.

A

vocal and articulate champion of rational urban planning who early on

saw the threat posed to the surrounding countryside by uncontrolled

sprawl and urban flight, Little was asked in 1954 to oversee the

development of a master plan for the revitalization of the blighted

area around St. Vincent Charity Hospital, beginning with new buildings

for that facility. His plan won Progressive Architecture’s urban design award. In the 1960s, he advocated the development of a

downtown transportation system to encourage Clevelanders to recognize

and build on such major assets as Public Square and University Circle.

In the early ’70s, he produced a plan for a jetport to be built on

landfill in Lake Erie, a futuristic if expensive vision.

A

vocal and articulate champion of rational urban planning who early on

saw the threat posed to the surrounding countryside by uncontrolled

sprawl and urban flight, Little was asked in 1954 to oversee the

development of a master plan for the revitalization of the blighted

area around St. Vincent Charity Hospital, beginning with new buildings

for that facility. His plan won Progressive Architecture’s urban design award. In the 1960s, he advocated the development of a

downtown transportation system to encourage Clevelanders to recognize

and build on such major assets as Public Square and University Circle.

In the early ’70s, he produced a plan for a jetport to be built on

landfill in Lake Erie, a futuristic if expensive vision.

Thinking outside the box was, after all, his trademark. “Bob Little was the guy who stuck his neck out,” says Blatchford, “and made it possible for the architects who followed him to practice modern architecture in this town.”